A subtype of inhibitory neurons in the mouse brain are activated when consuming a treat to assign value to the reward.

Vachez et al., Nature Neuroscience, 2021

In various disease states, such as depression, addiction, and obesity, the way our brains process rewards changes. Many people who suffer from these diseases experience a decrease in motivation. This symptom may be a result of experiencing anhedonia, which is when a reward that is usually considered valuable isn’t as enticing. But how do our brains decide how much value a reward has?

A team of researchers in the lab of Meaghan Creed, PhD, Associate Professor of Anesthesiology at Washington University in St. Louis, has uncovered the function of a subset of neurons in the ventral pallidum (VP) of mice, which they coined ventral arkypallidal neurons (vArky). The research article published in Nature Neuroscience describes how these neurons play a key role in promoting reward consumption and hedonic reactions. This discovery is an important step in decoding the circuitry behind the way animals assign value to a reward. This may help researchers pinpoint how reward signaling goes awry in various diseases as well as how these changes might affect motivation.

Previous studies have shown that the nucleus accumbens shell (NAcSh) and VP, both part of a region of the brain called the basal ganglia, are critical for reward processing. They partake in elaborate communication pathways both between themselves and other areas of the brain to decide the hedonic value of rewards. However, researchers were unsure about how coordinated activity within NAcSh and VP orchestrate reward valuation as well as where the source of NAcSh inhibition – which is necessary for reward consumption to occur – was coming from.

The magnitude of NAcSh inhibition scales with the hedonic value of reward. For example, if you really like ice cream, you could say that it has a high hedonic value and that consuming it causes your NAcSh to be highly inhibited while you’re enjoying it. The researchers reasoned that the VP is the source of NAcSh inhibition due to its previously known role of encoding motivation and reward value, in addition to research identifying a subset of neurons in the VP that project to NAcSh. Although previous studies had identified what the authors term vArky neurons, there was no research regarding these neurons’ functional purpose, or how precisely they were connected to the NAcSh. This missing piece helped form their hypothesis of vArky neurons being the source of NAcSh inhibition.

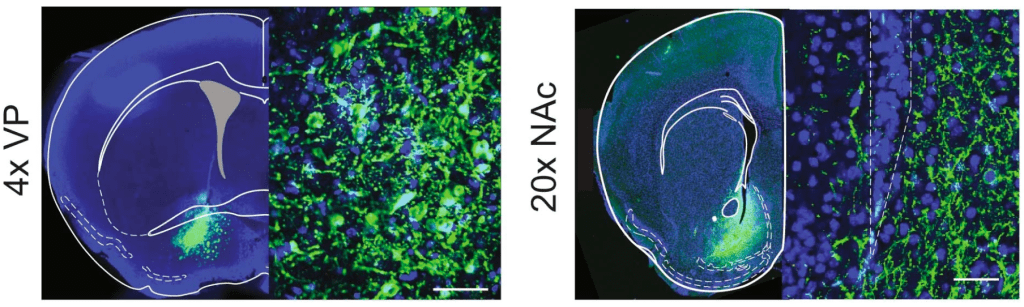

To test whether activation of vArky neurons promotes reward consumption, the researchers turned to a technique called optogenetics, which controls the activity of neurons using light. Scientists deploy viruses carrying the genetic code for light-sensitive ion channels called opsins to be expressed in neurons. The mice were injected with a virus that introduced an excitatory opsin specifically targeting vArky neurons. When activating these neurons, the researchers looked for changes in how long the mice spent drinking a delicious high-fat, high-sugar treat compared to no activation. They noticed that when these neurons are active, the mice would spend more time drinking the sweetened solution. Inhibitory opsins were injected into the NAcSh to show that inhibition is sufficient to promote reward consumption. These optogenetic experiments complement each other to suggest that vArky neurons are the source of NAcSh inhibition.

Another technique called fiber photometry was used to measure how much calcium is released within the vArky neurons. An implanted fiber detects calcium levels inside of neurons by measuring fluorescence emitted by a virally injected calcium-sensing protein. The amount of calcium detected indicates how active a neuron is; the more calcium there is, the higher the level of neuronal activity.

The researchers found that activity of vArky neurons scaled with the hedonic value of a reward, with activity increasing during reward approach and peaking right at the start of reward consumption. Subsequently, calcium signals from NAcSh decreased upon reward consumption which, paired with increased vArky activity, is consistent with the author’s hypothesis that the vArky neurons are inhibiting NAcSh activity.

Future studies will investigate which brain regions are sending signals to the vArky neurons. Mapping these reward pathways will further our understanding of how the NAcSh and VP assign hedonic value and shape behavior. Another step the researchers are taking is modeling how the vArky-to-NAcSh pathway fits into the basal ganglia to influence value and motivation in reward-seeking behavior. Diving into this specific pathway can identify how its activation can influence the motivation of reward-seeking behavior in disease as well as clarify the specific roles of the associated brain regions.

Michelle Lynch is a Neuroprep Postbacc Scholar in the lab of Meaghan Creed, PhD.